Context

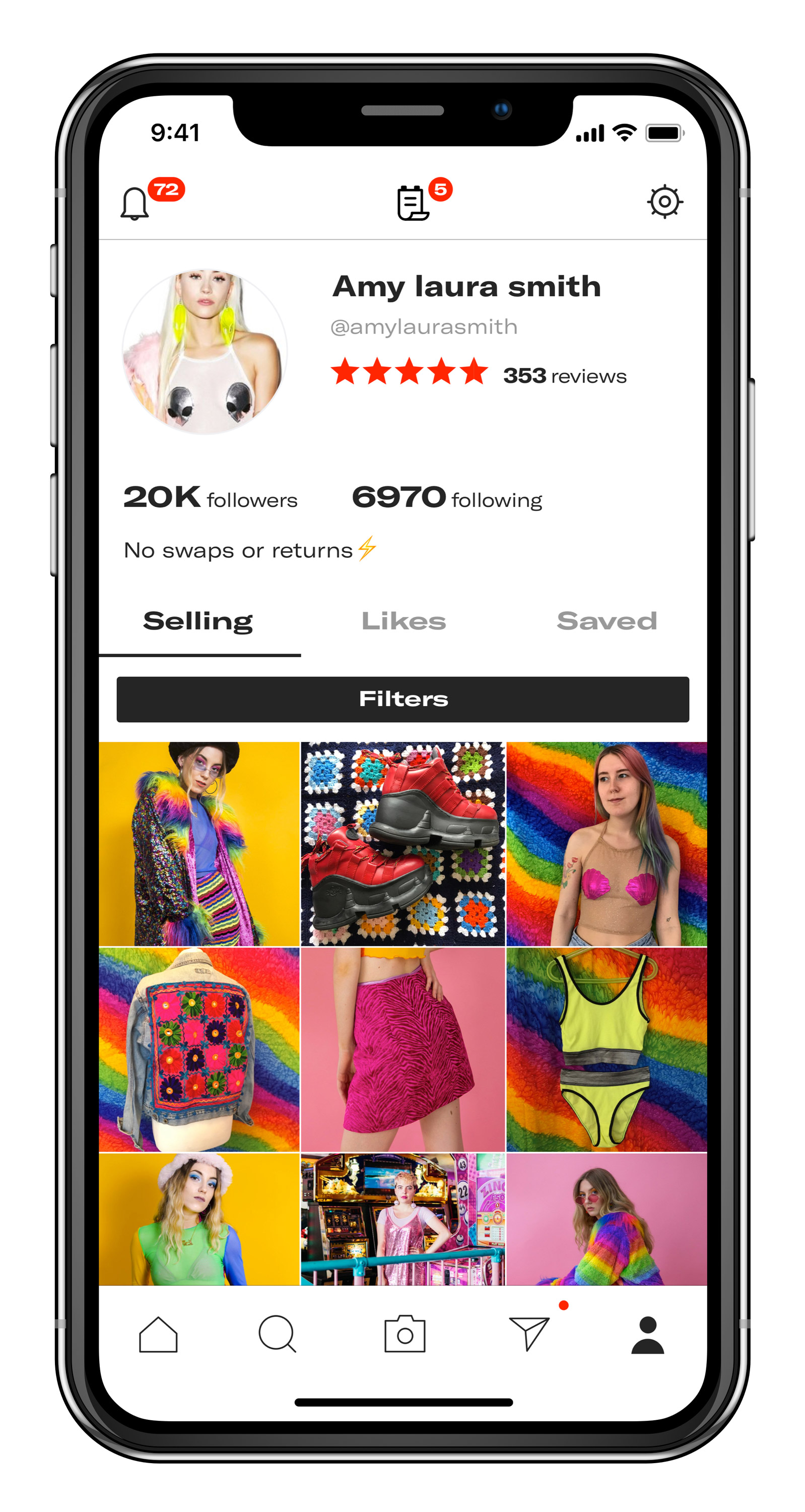

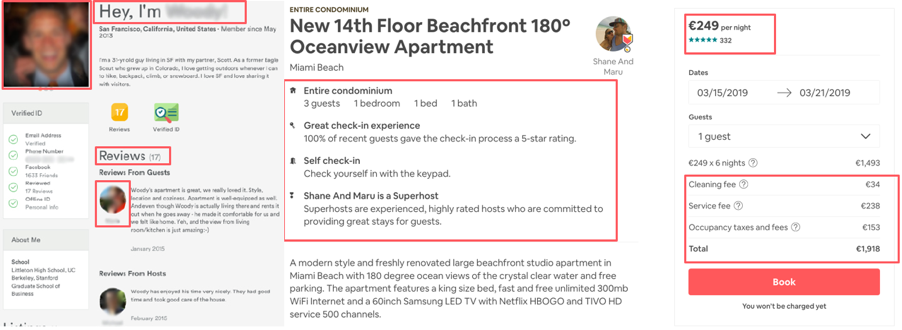

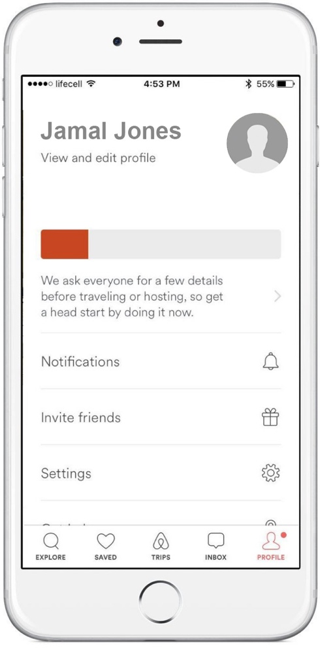

In the housing and rental market, anti-discrimination laws in the US gradually reduced discrimination through the legal system for the past two decades. However, academic scholars (Edelman, Luca & Svirsky, 2017) argue that the emergence of online platforms facilitate discrimination, as these laws do not reach smaller property owners using online platforms. Airbnb, the world largest online platform for short-term rental and housing, adopts a design choice that enables discrimination on its platform. Hosts decide whether or not to accept a guest after seeing the name and profile picture of the guest.

Methodology and experiment

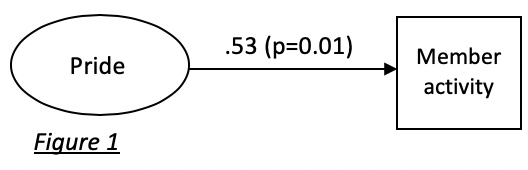

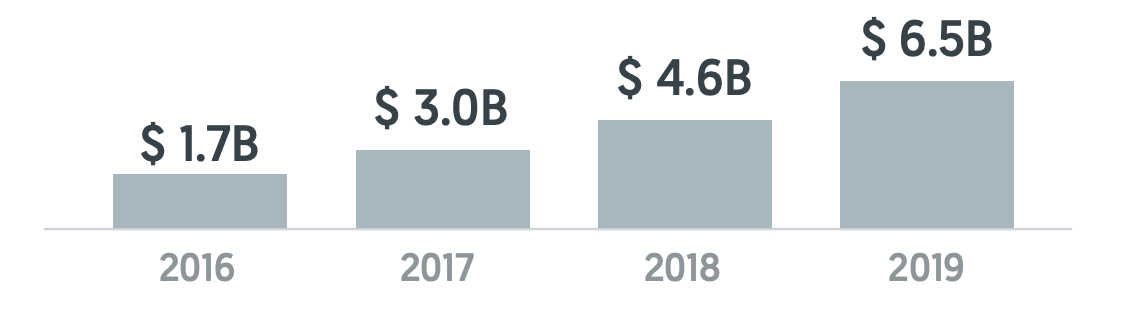

In order to test whether Airbnb facilitated discrimination through its design choice, the authors (Edelman, Luca & Svirsky, 2017) conducted a field experiment across five different cities, including: Baltimore, Dallas, Los Angeles, St. Louis and Washing DC between 7 July 2015 and 30 July 2015 (see Figure 1). Originally, the experiment aimed to gather data from the top 20 cities in the US, but the experiment was halted due to Airbnb’s systems detected and blocked the automated tools used to gather the data.

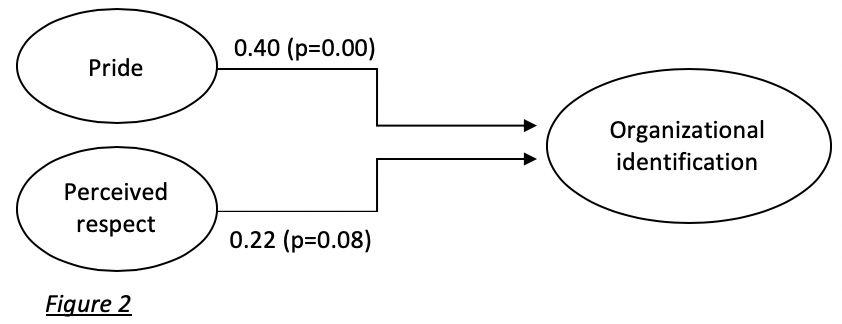

The experiment gathered a wide range of information about hosts and their listings (see Figure 2). Information of hosts include but are not limited to profile image, gender, age, number of properties listed and previous guests that visited the host. Information on listings include price, number of rooms, cancellation policy, cleaning fee, rating and whether the room was shared or not to control for interaction between the guest and the host.

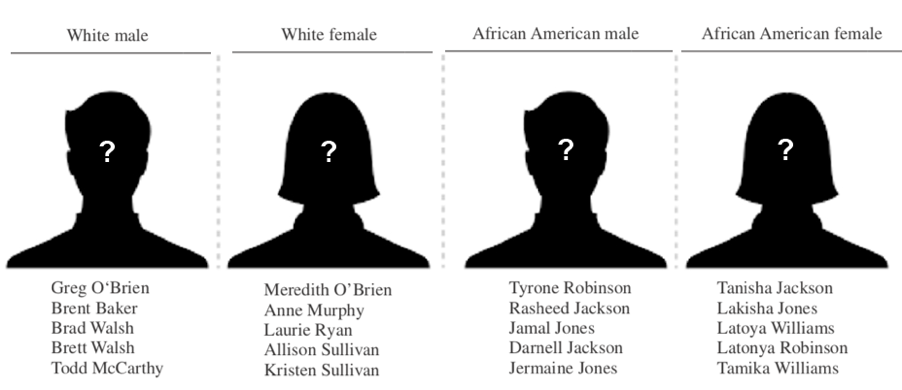

After gathering data, the experiment sent 6,400 messages with 20 Airbnb accounts. Hosts who offered multiple listings on the platform were contacted for one of their listings to prevent the host from receiving identical e-mails and to reduce the imposed burden. The accounts used to send messages are identical except for two variables: i) race and ii) gender. Race and gender were indirectly embedded in the profiles through the use of names based on Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004). Additionally, to alleviate confounds that would arise from using profile pictures, accounts did not include a profile picture. Finally, the experiment tracked the response over 30 days after the message was sent.

Results

The authors found that guests with distinctive White American sounding names were accepted ±50 of the time, while guests with African American sounding names were accepted at ±42 of the time. The ±8% gap persists across characteristics of the hosts and listings as control variables. More important, the results infer that the discrimination effect occurs in differences of a simple “Yes�? or “No�? response and not because of intermediate response and non-response. The authors further found that the discrimination effect disappears when hosts previously accepted African American guests. Control variables including homophily concerning race, age categories, price of the listing and demographics of the vicinity are however of no significant influence on the discrimination effect. Discrimination further cause financial consequences, as host incur costs when rejecting guests causes a unit to remain unrented.

Discussion: strengths and weaknesses

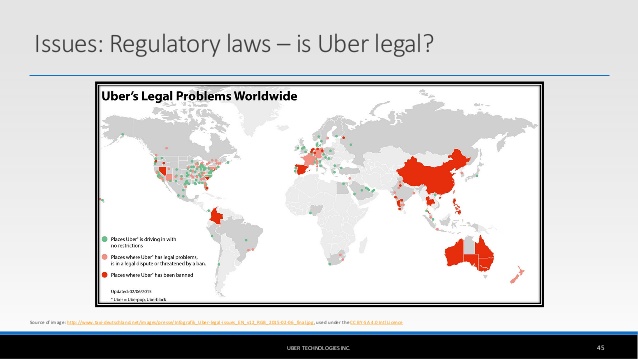

This paper provides clear evidence of the presence of discrimination in online platforms. The relevance of this paper is also strengthened by the way it emphasizes discrimination in the online channels, while in the past the focus was primarily on discrimination in offline channels. The results are consistent with other studies on discrimination in the online rental and housing market. Ge, Knittel, MacKenzie and Zoepf (2016) found a similar pattern of discrimination in peer transportation companies such as Uber and Lyft; African American passengers face longer waiting times and more frequent cancellations compared to their White-American counterparts.

The research also has a few flaws. First, the research is not able to detect the type of discrimination that occurs (e.g. statistical discrimination and taste-based discrimination) and whether discrimination is based on socioeconomic status or race that is associated with the name. Second, the paper suggests that the discrimination effect occurs when users of these platforms gain the choice to accept or to reject guests and passengers, which suggests that the problem lies in the platform’s design choice. The suggestions to alleviate discrimination by limiting design choice such as removing information of guests and passengers such as concealing names and profile photos or to eliminate the screening procedures by introducing instant book options as the only option, may harm the user experience for both (hosts and guests) sides. For hosts it is desirable if they can maintain control on who they allow to stay at their place, while for guests the platform is attractive if they can choose the place and host of their liking. When choosing to reduce discrimination by lowering the user experience for either party, online platforms run the risk of becoming less attractive than their competitors and jeopardizing their own competitiveness. Ultimately, discrimination will continue to occur on competing platforms that do not change their design in benefit of combatting discrimination and the non-discriminating company will lose its competitive edge and fail. Third, the inferences made by the paper are to a certain extent limited to the US. A recent study found that racial discrimination is more prominent in the US than in Europe (Pitner, 2018). The focus on metropolitan areas also questions whether the same effect will occur in rural areas. On the assumption that metropolitan areas are more globally connected and face higher exposure to other races, one can logically assume that metropolitan areas are more tolerant and discriminate less against other races.

Airbnb adjusted its non-discrimination policy in 2018. Hosts are no longer allowed to request a guest’s photo before accepting a booking agreement (Thinkprogress, 2018). Based on the research (Edelman, Luca and Svirsky, 2017), the adjustment will not help as hosts can still view names prior to the selection procedure. A potential solution is to increase the prevalence of reviews in the selection procedure. Cui, Li and Zhang (2016) found that encouraging credible peer-generated reviews mitigates the discrimination effect of guests with African American-sounding names on Airbnb. However, we argued that the action of one platform may not suffice as a solution to stop discrimination and call for more regulation on online platforms from authorities.

Airbnb adjusted its non-discrimination policy in 2018. Hosts are no longer allowed to request a guest’s photo before accepting a booking agreement (Thinkprogress, 2018). Based on the research (Edelman, Luca and Svirsky, 2017), the adjustment will not help as hosts can still view names prior to the selection procedure. A potential solution is to increase the prevalence of reviews in the selection procedure. Cui, Li and Zhang (2016) found that encouraging credible peer-generated reviews mitigates the discrimination effect of guests with African American-sounding names on Airbnb. However, we argued that the action of one platform may not suffice as a solution to stop discrimination and call for more regulation on online platforms from authorities.

Sources

Bertrand, M. & Mullainathan, S. (2004). “Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination.�? American Economic review 94 (4): 991–1013.

Cui, R., Li, J., & Zhang, D. (2016). Discrimination with incomplete information in the sharing economy: Evidence from field experiments on Airbnb.

Edelman, B., Luca, M., & Svirsky, D. (2017). Racial discrimination in the sharing economy: Evidence from a field experiment. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(2), 1-22.

Ge, Y., Knittel, C. R., MacKenzie, D., & Zoepf, S. (2016). Racial and gender discrimination in transportation network companies (No. w22776). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Pitner, B. H. (2018, May 17). Viewpoint: Why racism in US is worse than in Europe. Retrieved March 5, 2019, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-4415809

Thinkprogress. (2018). Airbnb announces booking policy change to head off outcry over persistent racial discrimination. Retrieved fromhttps://thinkprogress.org/airbnb-changes-photo-policy-combat-racial-discrimination-4f71c375553a/